B형 및 C형 간염에 대한 한약 치료의 효과 - 체계적 고찰 연구

Herbal Medicine for the Treatment of Viral Hepatitis B and C: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

Article information

Abstract

본 연구는 B형 및 C형 간염에 대한 한약 치료의 효과를 평가하기 위해 무작위 임상연구를 대상으로 체계적 문헌고찰 및 메타분석을 시행하였다.

검색엔진은 EMBASE, Pubmed, NDSL, KMBASE, KISS, KISTI, Koreamed, Koreantk, Oasis database를 이용하였으며 국내의 검색 엔진 키워드는 ‘간염’ 또는 ‘바이러스성간염’, ‘한약’, ‘무작위 배정 임상시험’을, 국외 검색 엔진 키워드는 ‘hepatitis’ or ‘viral hepatitis’ and ‘herbal medicine’ or ‘traditional chinese medicine’ and ‘randomized controlled trial’을 이용하였다.

연구 결과 15개의 무작위배정 임상시험을 선택되었으며, 그 중 통계적으로 유의미한 결과를 나타낸 연구는 한약과 양약 복합치료군이 양약을 투여한 대조군에 비해 HBV DNA loss에서 높은 효과를 보였다. 한약과 양약 복합치료군이 양약을 투여한 대조군에 비해 HBeAg loss에서 통계적으로 유의한 효과를 보였으며, 한약과 양약 복합치료군이 양약을 투여한 대조군에 비해 ALT가 감소하였다.

본 연구는 B형 및 C형 간염환자를 대상으로 한약의 효과를 확인하기 위해 기존에 시행된 RCT 연구를 대상으로 체계적 문헌고찰을 시행하였으며, 한약과 양약의 복합치료가 양약 단독치료에 비해 치료효과가 더 높은 것으로 나타났다.

Trans Abstract

The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that applied herbal medicine to treat viral hepatitis B and C in order to determine the therapeutic efficacy of herbal medicine.

EMBASE, Pubmed, NDSL, KMBASE, KISS, KISTI, Koreamed, Koreantk, and Oasis databases were searched to identify RCTs. The selected studies were assessed by the Cochrane group’s risk of bias tool.

A total of 15 RCTs were selected, and the hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA reduction was significantly higher in patients treated with herbal medicine combined with Western medicine than in patients treated with herbal medicine. Herbal medicine combined with Western medicine was also superior to Western medicine alone in achieving hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) and alanine aminotransferase [ALT] reduction. Only herbal medicine alone was not superior to Western medicine treatments in achieving HBV DNA, HBeAg, and ALT reduction.

I. Introduction

Hepatitis viruses (Type A, B, C, D, E) cause acute and chronic liver inflammation and they lead to asymptomatic inactivated infection, to fatal acute hepatitis or fulminant hepatitis1. They differ significantly in biology, disease progress and therapy options2.

Globally in 2015, hepatic viruses induced hepatitis caused 1.34 million deaths primarily from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma secondary to chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections3. Despite antivirus B treatment, it is difficult to expect complete eradication, so it is important to maintain the viral response for a long time4. Hepatitis C mostly transitions to chronic hepatitis without obvious clinical symptoms, which results in low recognition and delayed diagnosis, increasing the economic burden of the disease5. Thus, the treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis via complementary and alternative medicine for improvement in liver function and symptoms is increasing in popularity6.

Treatment of viral hepatitis falls under the following categories of Korean medicine: jaundice, aggregation-accumulation, distention and fullness7.

Although studies on viral hepatitis treatment have been published both inside and outside of Korea, there are a limited number of studies related to viral hepatitis treatment using herbal medicine monotherapy or combination therapy consisting of herbal and Western medicine. In addition, there are no systematic reviews of the clinical trials. Thus, this study aimed to review clinical trials that investigated the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine on viral hepatitis, and evaluate and provide evidence of the efficacy of this treatment via a meta-analysis.

II. Materials and methods

1. Participants

Herbal medicine articles published in and outside of Korea that investigated the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine in patients with viral hepatitis were included. The systematic review was performed using the participants, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design (PICO-SD) format8. In vivoand in vitro studies of non-human subjects, unoriginal studies, and studies published as abstracts only were excluded.

1) Participants : Patients with viral hepatitis (recorded characteristics including patient age, patient sex, and hepatitis B or C infection)

2) Intervention : Herbal medicine treatment

3) Comparison : Control groups not restricted

4) Outcome : Notrestricted

5) Study design : Randomized controlled trial (RCT)

2. Methods

1) Database selection and literature search

For studies published in Korea, literature searches were performed using the following Korean databases: the National Digital Science Library (http://www. ndsl.kr), Korean Medical Database (http://kmbase. medric.or.kr), Korean Studies Information Service System (http://kiss.kstudy.com), Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information Society (http://society.kisti.re.kr), KoreaMed (http://www. koreamed.org), Korean Traditional Knowledge Portal (http://www.koreantk.com), and Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (http://oasis.kiom.re.kr). The search terms were ‘간염’ or ‘바이러스성간염’, ‘한약’ or ‘한의학’, ‘임상시험’, ‘hepatitis’ or ‘viral hepatitis,’ ‘herbal medicine,’ and ‘randomized controlled trials.’

For studies published outside of Korea, literature searches were performed using PubMed (http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) and EMBASE (http:// www.embase.com). The search terms were ‘hepatitis’ or ‘viral hepatitis,’ ‘herbal medicine’ or ‘traditional Chinese medicine,’ and ‘randomized controlled trial.’

2) Study selection

Two researchers (LYR and CNK) independently performed the literature search and study selection. The identified studies were collected and duplicates were excluded. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the studies were initially selected by examining their titles and abstracts. The full texts of the studies were then evaluated to select RCTs that investigated the use of herbal medicine for the treatment of viral hepatitis. In cases of disagreement between the two researchers, a third researcher (KKS) intervened and a consensus was reached by majority vote.

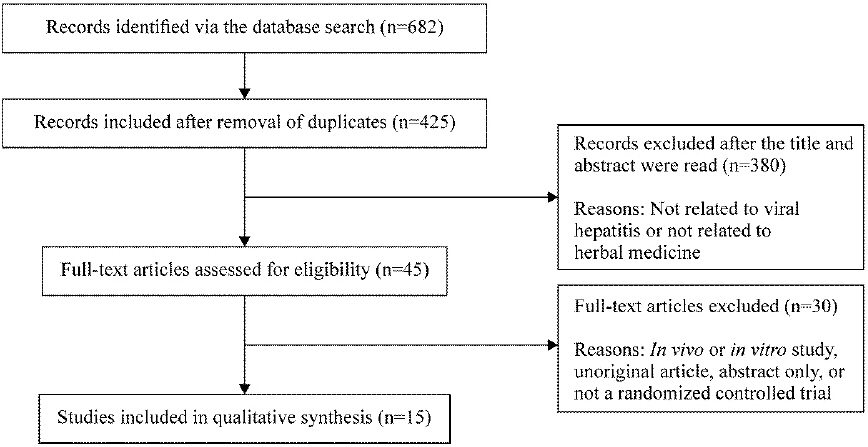

The literature search was conducted from August 1 to August 3, 2018. Studies published up to July 2018 were included, with no restrictions on language (Fig. 1).

3) Data analysis

After two reviewers (LYR, CNK) reviewed the full text of the selected studies, data regarding the publication year, number of study participants, method and duration of treatment in intervention and control groups, measurement instruments, treatment outcomes, and reports of adverse events were extracted from each study. Based on the extracted data, the characteristics of each study were reviewed.

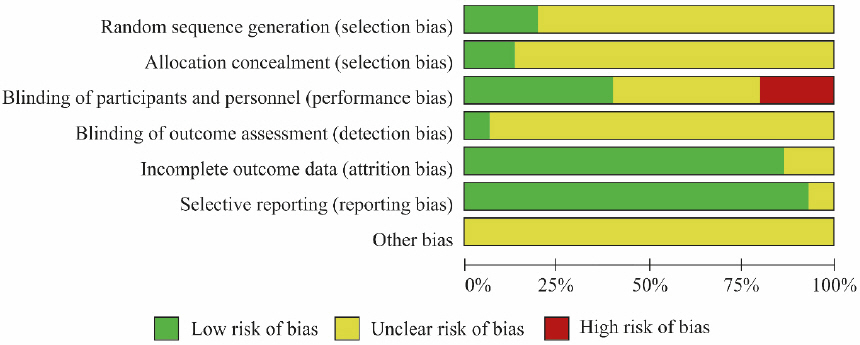

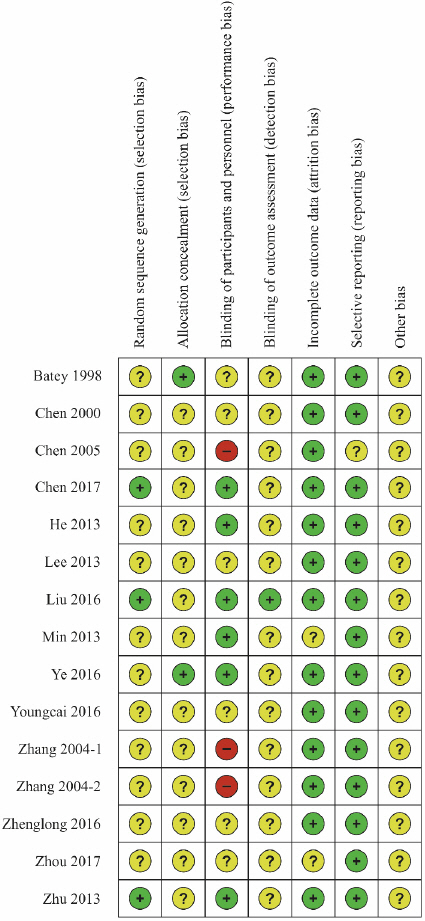

4) Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) tool was used for the risk of bias assessment, as only RCTs were reviewed in this study9. This tool includes seven domains of assessment: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of the outcome assessor, handling incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias that threaten the validity of the study findings. For the detailed criteria of each domain, the National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaborating Agency guidelines for systematic reviews were used9.

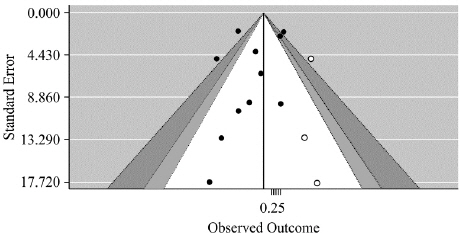

5) Publication bias

Publication bias is a type of reporting bias that occurs when there is an association between the possibility of publishing and the statistical significance of the study results. It is generally represented by a funnel plot, and Egger’s regression test was performed as a statistical test for publication bias.

6) Meta-analysis

Statistical analysis of the studies included in the systematic review was performed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s RevMan (Review Manager) version 5.3. The odds ratio (OR) and a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) were used for binary outcome data, while the mean difference (MD) and a 95% CI were used to measure the effect size for continuous outcome data. After assessing heterogeneity using Higgin’s I2, twomodels, fixed-effects (in I2=0% or not applicable) and random-effects (in I2≠0%), were used to combine the summary statistics.

III. Results

1. Data selection

Literature search using a total of nine databases from August 1 to August 3, 2018 identified a total of 425 studies. After reviewing the titles and abstracts of these studies, 380 studies not related to viral hepatitis and herbal medicine were excluded. The 45 studies that were initially selected were read in detail, and 1510-24 studies were finally selected (Fig. 1).

2. Data analysis

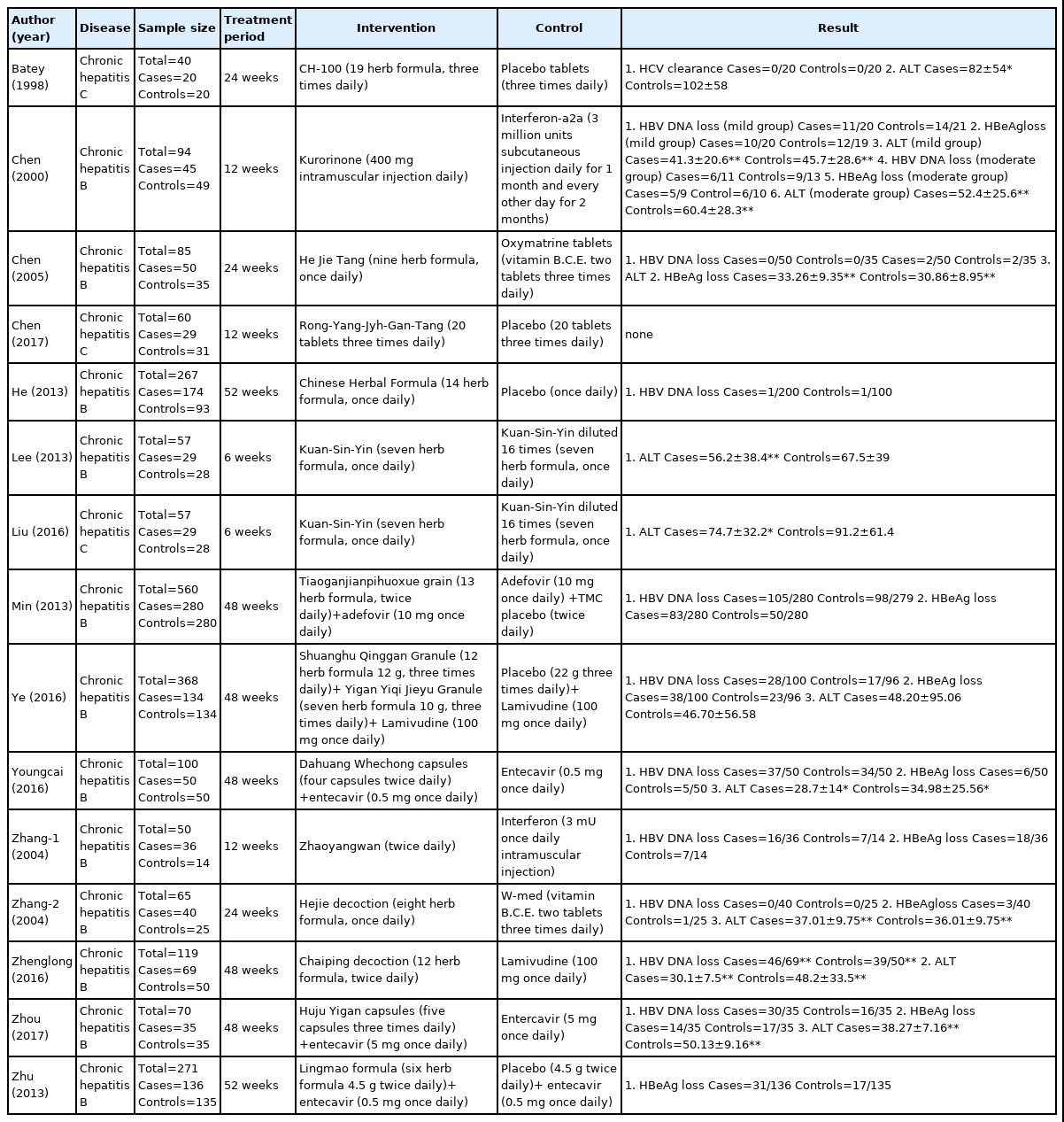

Of the selected studies, 11 were conducted in China, three were conducted in Taiwan, and one was conducted in Australia. Participants, treatment methods, outcomes of interventions, and control groups were assessed (Table 1).

1) Study design

Twelve studies investigated hepatitis B, while three studies investigated hepatitis C. Of the 12 studies that investigated hepatitis B, five compared herbal medicine to Western medicine, one compared herbal medicine to a placebo, one compared herbal medicine to diluted herbal medicine, and five compared combination therapies of herbal and Western medicine to Western medicine monotherapy. All studies on hepatitis C compared herbal medicine to placebos.

2) Treatment group and control group

(1) Treatment duration and participants

The duration of treatment varied from 6 to 52 weeks. The total number of participants was 2263, the mean number of participants was 191.1, and the standard deviation for the number of participants was 150.2. Of these, the mean number of participants was 94.9 for the experimental group and 86.7 for the control group.

(2) Herbal medicine interventions

The herbal medicines used for the interventions are provided in Table 2.

(3) Control group interventions

Generally, antiviral agents were used as the treatment method in the control groups. Entecavir was used in three studies, interferon α and lamivudine were each used in two studies, and adefovir was used in one study. A mixture of vitamin B, vitamin C, and vitamin E was used in two studies.

3) Outcome measures

Four outcome measures related to viral hepatitis (hepatitis B virus [HBV] DNA, hepatitis B e-antigen [HBeAg], hepatitis C virus [HCV] RNA, and ALT reduction) were used in the selected studies. HBV DNA reduction was used in 11 studies, HBeAg reduction was used in nine studies, HCV RNA reduction was used in two studies, and ALT reduction was used in ten studies. A meta-analysis was performed using the rate of HBV DNA, HBeAg, HCV RNA, and ALT reduction as outcome measures.

4) Treatment outcomes

(1) HBV DNA reduction

A total of 11 studies12,14,17-24 were included in the HBV DNA reduction assessment. Depending on the type of intervention, the studies were divided into subgroups and assessed. The participants of Chen’s study12 were divided into mild, moderate, and severe groups, and the outcome data of Chen’s study12 were analyzed using only the mild and moderate groups because the severe group was excluded from Chen’s study12 (Table 3).

① Herbal medicine vs Western medicine

Five RCTs11,12,20-22 were included. The HBV DNA reduction was significantly lower in the herbal medicine groups than in the Western medicine groups (Fig. 2). Heterogeneity was not detected among the studies (OR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.96, p=0.04, I2=0%).

Results of the meta-analysis for hepatitis B virus DNA reduction (herbal medicine vs Western medicine).

② Herbal medicine vs placebo

One study14 was included. The HBV DNA reduction was lower in the herbal medicine group than in the control group treated with a placebo (Fig. 3). However, the difference was not statistically significant (OR=0.50, 95% CI: 0.03 to 8.04, p=0.62).

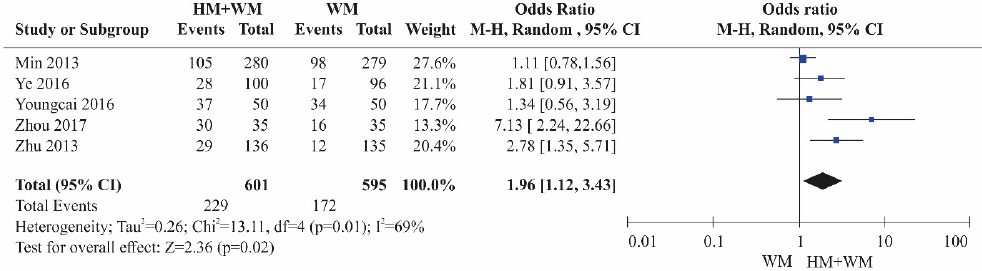

③ Herbal medicine+Western medicine vs Western medicine alone

Five RCTs17-19,23,24 were included. The HBV DNA reduction was significantly higher in the combination therapy groups (herbal medicine+Western medicine) than in the control groups treated with Western medicine alone (Fig. 4). Heterogeneity was high among the studies (OR=1.96, 95% CI: 1.12 to 3.43, p=0.02, I2=69%).

Results of the meta-analysis for hepatitis B virus DNA reduction (herbal medicine+Western medicine vs Western medicine).

(2) HBeAg reduction

Nine studies11,12,17-21,23,24 were included in the HBeAg reduction assessment. The studies were divided into subgroups according to the type of intervention and assessed. Chen’s study12 was analyzed in the same manner as in the HBV DNA reduction assessment.

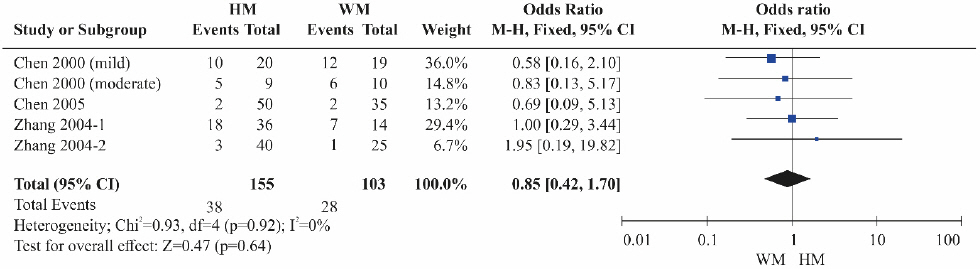

① Herbal medicine vs Western medicine

A total of four RCTs11,12,20,21 were included. Although the HBeAg reduction was lower in the herbal medicine groups than in the Western medicine groups, the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 5). Heterogeneity was not detected among the studies (OR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.42 to 1.70, p=0.64, I2=0%).

Results of the meta-analysis for hepatitis B e-antigen reduction (herbal medicine vs Western medicine).

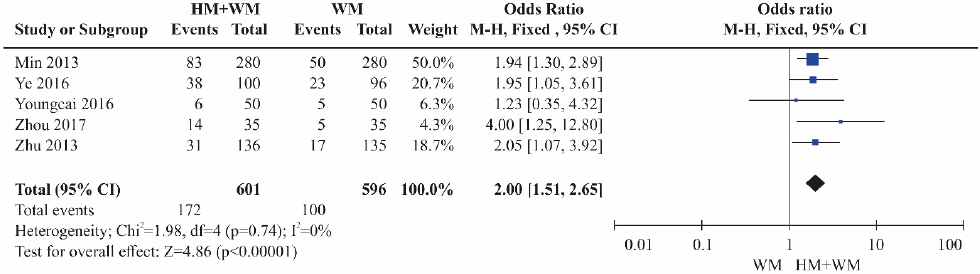

② Herbal medicine+Western medicine vs Western medicine alone

Five RCTs17-19,23,24 were included. The HBeAg reduction was significantly higher in the combination therapy groups (herbal medicine+Western medicine) than in the control groups treated with Western medicine alone (Fig. 6). Heterogeneity was not detected among the studies (OR=2.00, 95% CI: 1.51 to 2.65, p<0.001, I2=0%).

Results of the meta-analysis for hepatitis B e-antigen loss (herbal medicine+Western medicine vs Western medicine).

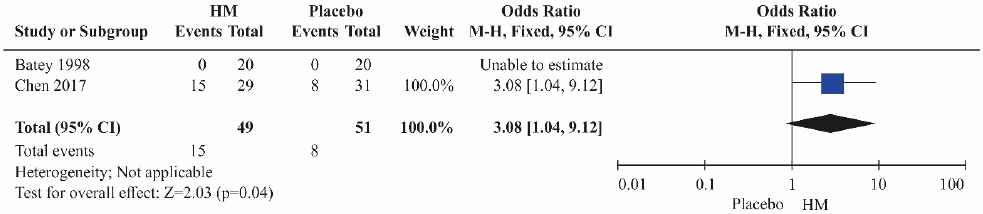

(3) HCV RNA reduction

Two studies10,13 were included in the HCV RNA reduction assessment. Both studies compared herbal medicine to placebos. The HCV RNA reduction was significantly higher in the herbal medicine groups than in the control groups treated with placebos alone (Fig. 7; OR=3.08, 95% CI: 1.04 to 9.12, p=0.04).

(4) ALT

Ten studies10-12,15,16,18,19,21-23 were included in the ALT assessment. The studies were divided into subgroups according to the type of intervention and assessed. Chen’s study12 was analyzed in the same manner as in the HBV DNA reduction assessment.

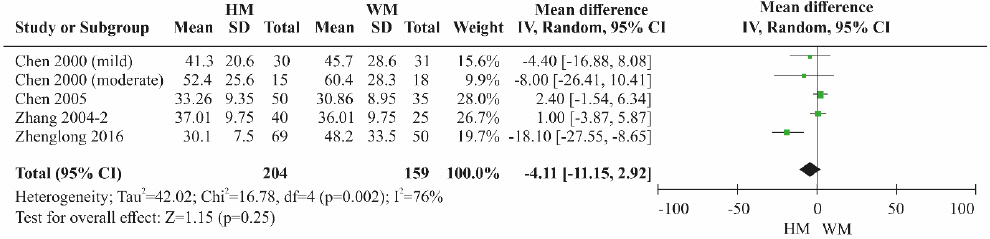

① Herbal medicine vs Western medicine

A total of four RCTs11,12,21,22 were included. Although the ALT level was lower in the herbal medicine group than in the control group treated with Western medicine, the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 8). High heterogeneity was detected among the studies (MD=-4.11, 95% CI: -11.15 to 2.92, p=0.25, I2=76%).

② Herbal medicine vs placebo

A total of two RCTs10,16 were included. Although the ALT level was lower in the herbal medicine groups than the control groups treated with placebos, the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 9). Heterogeneity was not detected among the studies (MD=-17.73, 95% CI: -38.33 to 2.87, p=0.09, I2=0%).

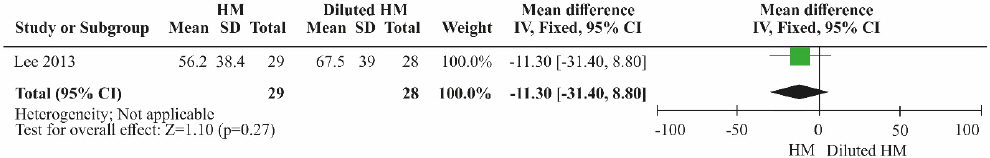

③ Herbal medicine vs diluted herbal medicine

One RCT15 was included. Although the ALT level was lower in the herbal medicine group than in the control group treated with diluted herbal medicine, the difference was not significant (Fig. 10; MD=-11.30, 95% CI: -31.40 to 8.80, p=0.27).

Results of the meta-analysis for alanine aminotransferase (herbal medicine vs diluted herbal medicine).

④ Herbal medicine+Western medicine vs Western medicine alone

Three RCTs18,19,23 were included. The ALT level was significantly lower in the combination therapy groups (herbal medicine+Western medicine) than in the control groups treated with Western medicine alone (Fig. 11). Low heterogeneity was detected among the studies (MD=-10.42, 95% CI: -13.83 to -7.00, p<0.001, I2=36%).

5) Bias assessment

Risk of bias assessment was performed on the 15 studies selected for the analysis using Cochrane’s RoB tool (Fig. 12, Fig. 13). Three studies13,16,24 that used tables of random numbers were classified as having a low risk of bias. Onestudy10 that used identically-shaped packages with serial numbers and one study15 that used independent central randomization were classified as a low risk of bias. Six studies13,14,16-18,24 that employed double blinding were classified as a low risk of bias, while three studies12,20,21 that compared decoction, capsule, and injection administration methods were classified as having a high risk of bias since blinding was not possible. One study16 that employed blinding of the outcome assessor was classified as having a low risk of bias. Thirteen studies10-16,18-22,24 that reported all reasons for and numbers of dropout participants or without missing data were classified as a low risk of bias. In the selective reporting domain, 14 studies10,11,13-24 that reported the study protocol or all expected outcomes were classified as a low risk of bias. Studies were classified as unclear risk for all other assessment domains if no details were reported.

6) Publication bias

Examination of the contour-enhanced funnel plot revealed that the plot was visually symmetrical (Fig. 14). In addition, the results of Egger’s regression analysis indicated that there was no potential for publication bias (t=-0.76519, df=9, p-value=0.4637)25.

7) Safety

Of the 15 studies selected, cases of participant dropout due to the occurrence of serious adverse events were identified in four studies10,14,18,24. Participants dropped out from the experimental group in three studies10,14,24 and from the control group in two studies18,24. Symptoms of adverse events included increased ALT levels, decreased lymphocytes levels, palpitations, and diarrhea.

The funnel plot is centered at 0, the value under the null hypothesis of no effect. The region outside of the funnel corresponds to p-values of <0.01, the dark gray shaded region corresponds to p-values between 0.05 and 0.01, the gray shaded region corresponds to p-values between 0.10 and 0.05, and the white region in the middle corresponds to p-values of >0.10.

IV. Discussion

The present study consisted of a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine on viral hepatitis B and C. The selected studies included RCTs of herbal medicine monotherapy and combination therapy of herbal and Western medicine in patients with viral hepatitis B and C. The therapeutic effect of herbal medicine was assessed in 15 studies using four outcome measures (HBV DNA, HBeAg, HCV RNA, and ALT reduction).

RCTs and meta-analyses regarding herbal medicine treatment of viral hepatitis have not yet been conducted in Korea. With regard to studies in China, several meta-analyses have examined the therapeutic effects of herbal medicine treatment on chronic hepatitis C26,27, HBV-relatedlivercirrhosis28,29, and HBV carriers30. One study on the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine on hepatitis C found that combination therapy of herbal medicine and interferon-α resulted in a higher sustained virologic response (SVR) than did herbal medicine monotherapy (49% vs 33%, relative risk 1.52; 95% CI: 1.23 to 1.89; p<0.05)27. Studies on the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine treatment on HBV-related liver cirrhosis indicated that herbal medicine treatment was more effective in lowering the levels of biochemical factors related to liver cirrhosis than conventional Western medicine treatment28.29. Herbal medicine and Western medicine combination therapy was more effective in decreasing HBeAg seroconversion than Western medicine monotherapy in HBV carriers (relative risk 4.67, 95% CI: 1.36 to 15.98; p=0.01; p=39%)30. Based on the findings of these previous studies, it was confirmed that herbal medicine treatment may be useful in clinical practice and has a high therapeutic effect, particularly when combined with antiviral agents. However, there were limitations in that the number and quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis were low.

Of the 15 studies included in the present study, 12 were related to chronic hepatitis B and three were related to chronic hepatitis C. Most of the studies were conducted in China. Herbal medicine treatment was provided in various forms, including granules, tablets, decoctions, and injections. In studies wherein the composition of the herbal preparations used in the treatment was described, Glycyrrhiza uralensis was the most commonly used compound (used seven times) followed by Salvia miltiorrhiza BUNGE, Bupleurum falcatum L., Scutellaria baicalensis, Astragalus membranaceus, Pinellia ternata Breitenbach, Polygonum cuspidata SIEB. et ZUCC., Polyporus umbellatus FR, and Atractylodesjaponica Koidzumi. Glycyrrhiza uralensis serves to harmonize the ingredients of all drugs31, and its use was confirmed in most of the prescriptions. In oriental medicine, “To clear heat and drain dampness” is the primary treatment method for viral hepatitis7, and herbal preparations were used. Each of the studies used different herbal preparations, and it is speculated that this was due to modified formula of traditional herbal medicine. In 10 of the studies, Western medicine was used as the intervention in the control group. Western medicine used antiviral agents, such as entecavir, interferon-α, lamivudine, and a defovir, and a vitamin B, vitamin C, and vitamin E mixture.

The ultimate treatment goals for patients with chronic hepatitis B who are HBeAg-positive or -negative are normal ALT levels, undetectable HBV DNA levels, and a reduction or conversion of serum HBeAg32. The goal of antiviral treatment for hepatitis C is to achieve an SVR, wherein HCV RNA is undetectable in the serum by a sensitive assay at 12 or 24 weeks after the completion of treatment32. Thus, the present study examined four outcome measures (HBV DNA, HBeAg, HCV RNA, and ALT reduction) and found that the outcome measures of HBV DNA, HBeAg, HCV RNA, and ALT reduction were used in 11, nine, two, and 10 studies, respectively.

The results of the meta-analysis indicated that the HBV DNA reduction was significantly lower in the groups treated with herbal medicine alone than in the groups treated with Western medicine. Herbal medicine treatment was also less effective than placebos. A comparison of the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine and Western medicine combination therapy to that of Western medicine monotherapy revealed that combination therapy had a significantly greater therapeutic effect than did monotherapy. However, heterogeneity was high among the studies. Although the HBeAg reduction was lower in the herbal medicine monotherapy groups than in the Western medicine groups, the difference was not statistically significant. A comparison of the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine and Western medicine combination therapy to that of Western medicine monotherapy revealed that the HBeAg reduction was significantly higher in the combination therapy groups.

A comparison of the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine to that of placebo on HCV RNA reduction revealed that the HCV RNA reduction was significantly higher in the herbal medicine groups than in the control groups treated with placebos. Although the ALT level was lower in the herbal medicine groups than in the three control groups treated with Western medicine, placebos, and diluted herbal medicine, the differences were not statistically significant. Also, herbal medicine and Western medicine combination therapy was significantly more effective in lowering the ALT level than Western medicine monotherapy.

There were no significant difference in the HBV DNA, HBeAg, and ALT reduction between herbal medicine monotherapy and Western medicine monotherapy. However, herbal and Western medicine combination therapy was significantly more effective in achieving HBV DNA, HBeAg, and ALT reduction than was Western medicine monotherapy. Therefore, it would be useful to conduct additional clinical studies comparing herbal medicine and Western medicine combination therapy to Western medicine monotherapy.

V. Conclusions

The present study performed a systematic review of RCTs to investigate the therapeutic effect of herbal medicine in patients with viral hepatitis B and C. However, this study has several limitations. Bias assessment of the studies was difficult, as most studies did not mention the details required to assess bias. The total number of RCTs included in the study was limited to 15, and there were only three RCTs on hepatitis C, so the interpretation should be regarded carefully. And this study analyzed papers p to 2018. Now still, there is no RCT using herbal medicine implemented in Korean hepatitis patients. So, a future study with higher standards that addresses this issue is needed.

The results indicated that herbal medicine and Western medicine combination therapy is more effective than Western medicine monotherapy. Currently, most patients with viral hepatitis seek oriental medicine for symptom relief after receiving antiviral therapy. Notably, based on the findings of this study, adjunctive herbal medicine therapy for the treatment of viral hepatitis may be beneficial. This result could be beneficial in increasing the treatment rate of viral hepatitis clinical practice in herbal medicine. This study’s findings may serve as the basis for future clinical research designs in Korea.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2018R1A5A2025272).